The change curve

Let me tell you a story about a thing called the change curve.

It’s a story I can only tell now, months after the events unfolded, because it’s taken that distance to work out what the hell was going on.

And to start we’re going to have to slip back in time…

A time before the fall

Rewind my life one year. I’d just survived the first 12 months of working for a proper UX agency. No one had found me out as an impostor. I’d done some good work and developed more as a user experience designer than I ever expected to in that time. In fact, almost exactly a year ago, I gave a talk at UX Lisbon to a group of designers about my approach to prototyping. It went down really well.

I was on top of the world and hungry for more responsibility.

In short succession I started line managing people for the first time in my life, got promoted to lead the user experience designers in our London office, and began leading a project team of multiple designers on a huge, complicated, high profile, and interesting project.

This sequence of events propelled me onto the change curve. So let’s quickly explain what the change curve is and then we can get on with the story.

The Kübler-Ross model

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was a Swiss-American psychiatrist who did a lot of influential work related to death and dying in the 1960s. She was all about helping people to confront the reality of terminal illness and death, which is pretty high on my list of worthwhile life missions.

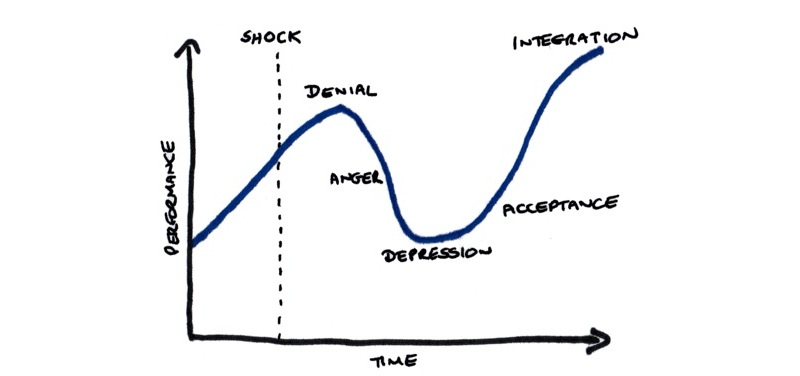

You already know Kübler-Ross’s work because it’s the five stages of grief. Denial. Anger. Bargaining. Depression. Acceptance. She unveiled these stages in 1969, but over time they’ve come to be used for much more than modelling the stages of grief.

These days the five stages have evolved into the change curve below, which is used as a method of helping people understand their reactions to significant change or upheaval.

Riding the curve

Before I dropped into the change curve I’d spent five years improving my design and research skills with tangible results. As my performance increased over time, so did my confidence in my skills and my future ability to keep improving. A year ago I was confident, happy and hopeful about the future.

But that was all about to change.

First came the shock, a major change that sent me hurtling into the change curve. In my case this was taking responsibility for other people’s output, their happiness at work, and their development as designers. Up until that point I’d only ever had to focus on my own output, happiness and development - but when I started focusing on supporting other people, the tools and methods I had used on myself were clearly insufficient and I had very little idea what to do.

The denial came next. The honest truth is I never even registered the shock at the time. For months and months I thought I was doing a wonderful job when in fact the quality of my project work was slipping and I was treating my colleagues like children. The thing about denial is that it’s incredibly, invisibly powerful - you would think you’d spot it in yourself but you don’t. In the end it took some very direct feedback from my colleagues and my girlfriend to help me realise just how much I was struggling.

Then flowed the anger. And boy did I get angry. With the job. With the project. With my colleagues. With my girlfriend. With the prototype I was building. And, on one unforgettable late night, with a web font that simply would not work when I uploaded it to the server. The thing about the angry stage is it’s happening right when your performance is falling off a cliff, so it’s a powerful front to avoid taking responsibility for the way things are going wrong. It’s the part of the change curve that I am most ashamed of when I look back.

The depression quickly followed. For me this set in once the crunch project was over, and it sat with me for a while because I went away to New Zealand for a month. It was not my happiest holiday ever. During that time I started to glimpse what had really been going on: I was out of my depth and didn’t know what to do about it. They say that the depression stage is a kind of early-acceptance but one where you are still emotionally attached to the things you are accepting, which is what makes it so fucking difficult. I kind of feel like I don’t need to tell you about depression. It’s the very bottom of the change curve for a reason.

And, eventually, the acceptance. After New Zealand, and after another painful four weeks on the project, I started to privately and publicly accept the scale of my failure and own up to the many things I had done wrong. Honestly, this all started from some brave, direct feedback from my colleagues in a sprint retrospective. I gradually saw the scale of the task ahead of me, which was that taking responsibility for more than my own work required a radical rethink about how I approach the act of work in general. I stopped being in denial. I stopped being angry. And although it sounds like this would make you more depressed, actually holding my hands up and saying these things are my fault was a huge relief, so I left the depression behind as well.

Finally, integration. This is where you experiment with new approaches and then adopt the ones that help you raise your performance in your new, changed, situation. I’ve been doing a lot of thinking, reading, training, and experimenting in the art of leading teams. I’ve been doing a lot of listening too. Some of it works, some of it doesn’t, but my future feels interesting and hopeful again. It’s not the same future that I envisaged a year ago - lots more about working effectively with other people and lots less about interaction design patterns and research methods - but that’s the thing about change: it does involve making changes.

Mental models for mental problems

It’s been a rough year if I’m honest.

But I can pinpoint exactly when things turned around. At about 4.00pm on Thursday 16 April someone that I trust scribbled this change curve down on a piece of paper and said, look, Will, this is what you have been going through.

In an instant, my whole year made sense. I saw my life on that curve - shock, denial, anger, depression, acceptance - and it gave me a sudden burst of hope that there was a way forward.

I love a simple model that helps us understand a messy situation. I love being able to put the right words on complicated things in a way that brings a sudden clarity.

That’s why I wanted to share this story. Maybe it’ll do the same for you.

Thanks to everyone who went on this journey with me, but in particular to those who gave me the feedback I needed. You know who you are.