Building Local Welcome by tackling our riskiest assumptions

This is the written-up version of a talk I gave at Service Design in Government 2020. It’s the first time I’ve given a talk about being a product manager.

Local Welcome is a tiny startup charity. We run meals at the weekends where we bring together refugees and local people for two hours to cook and eat a meal.

Local Welcome meals are not about feeding refugees, or doing things for refugees. There are many charities that do that. But that’s not us. We’re about creating a space where refugees and local people can come together as equal human beings. This means we are interested in reducing the power dynamics as much as possible.

That’s why we use food. Preparing and eating food together is a universal human experience. It reduces barriers to getting to know each other. It makes it easier when you don’t speak the same language. It reduces the pressure on people that feel shy.

Our meals are fun. They reduce loneliness, increase personal confidence, help people understand other cultures, change eating habits, strengthen social connections, and build much-needed social capital.

But Local Welcome meals haven’t always been like this.

Local Welcome was founded in 2015 by Ben Pollard. He started by bringing Syrian refugees and people that wanted to help refugees together in Starbucks up and down the country. He realised that you can’t just bring people together and expect them to get on. You need something for people to do together.

We hit on using food to bring people together. It started with pizzas, moved on to pancakes, and ended up with whole meals. By prototyping, learning, and iterating we ended up at the two-hour meal that we love and are using today.

By the end of 2017 we knew we could run wonderful meals at a small scale.

In 2018 the National Lottery Community Fund gave us money to scale these meals across the whole of the UK.

The Lottery funded us to build a multidisciplinary team that included product, design, delivery, technology, operations and communications. They were interested in how approaches from the worlds of user-centred design and digital technology might work in small charities.

The Lottery were also interested in our self-funding model. Our proposal was to build Local Welcome so that it was funded by the people that came to our meals. Not by the refugees, because they have very little money, but by the local people.

In November 2018 I joined Local Welcome as the product lead. Before I tell you about that there are two things I need to mention.

The first is about how I use the word ‘refugee’. I’ve used it a few times already.

When I say refugee I mean a person who has been forced to leave their country to escape war, persecution, or natural disaster. I think this is the common, everyday meaning of the word. When you read the word in a book, hear it in a film, or see it on the news this is what most people think it means.

But there is another definition. The Home Office uses the word ‘refugee’ to refer to someone that the UK Government agrees has legitimately been forced to leave their country. They call this ‘refugee status’.

This creates other statuses. When people first arrive they are ‘asylum seekers’ (or, better, ‘people seeking sanctuary’). If the Home Office decides you are not legitimate there are other terms. Like ‘failed asylum seeker’ or ‘destitute asylum seeker’.

I don’t care about the UK Government’s judgement. When I say ‘refugee’ I include all of these different people and statuses.

The other thing is to share a little bit about me. You should know where I’m coming from so you know whether to listen to me or not. There are three things to know.

First, I only became a product manager recently. Local Welcome is my first full-time product role. I’m still learning what it means. Take everything I say with a pinch of salt.

Secondly, I’ve worked in many ways. As product manager, user researcher, interaction designer, user experience designer, frontend developer and communications person. In the private sector for multinational corporations, public sector for GDS and the Home Office, and now in the charity sector. Waterfall, agile, agency, consultant and in-house. From being the only person in the cxpartners London office up to being one of tens of thousands at the Home Office. I say this to show that I am not wedded to any one viewpoint. They all have positives and negatives. None are right.

Thirdly, I am obsessed with making an impact. I have been frustrated with how little impact my work has had throughout my career. I started feeling this at agencies and I wrote lots about it. I moved in-house to see if being part of a multi-disciplinary team might help. I’ve moved to a tiny startup to answer the same question.

I’m going to start by going through how a Local Welcome meal works. There are three groups of people at our meals.

3 leaders. Leaders are local people who arrive early to set up the room, lead the food preparation and keep conversation flowing. They are like facilitators. They pay £5 per month and have done a DBS check and our safeguarding training. Each of them leads one meal a month.

9 members. Members are local people who get £5 tickets to come to the meal. They come as often or as little as they like. Some come once and decide it’s not for them. Others come again and again.

9 refugee guests. Guests also get tickets to come to the meal but the tickets are free. Guests also come as often or as little as they like. Guests and members are the same except for the payment.

There are three tables set up at the meal. Each table is set up to make a different recipe. For example, chickpea salad, potato rosti and tabbuleh. All the food and equipment needed to make the recipe is laid out on the tables.

Each table has a leader who guides the group through a seven step recipe. Each step has a question to get the conversation going. The questions are designed to be safe.

Each table has three cooking pairs. Each cooking pair is a local person and a refugee guest. They have their own cooking station - basically a chopping board and knife - and the pair works together on each recipe step. For example, chop an onion.

After about 45 minutes the three tables finish making their recipes.

When the recipes are made we push the tables together, lay out the food, and eat the whole meal as one big group. This is our group eating in Derby.

After we finish eating we wash up and pack away together. It’s during this last 30 minutes that the best conversations happen. People feel at ease.

This whole thing is like a technique called 1-2-4-All from Liberating Structures:

Arrive on your own (1)

Pair with someone to make food (2)

Get to know your table as you make food (7)

Eat and tidy up as a big group (all).

This means that people, even shy people, feel safe when meeting new people and feel OK about joining the bigger group. That’s what makes our meals wonderful.

In January 2019 we knew how to run wonderful meals on a small scale. Our task was to scale up so that there were enough meals across the UK to get us to self-funding.

The big question was how are we going to do this?

We had a hypothesis. This was the basis of our Lottery proposal in 2018.

The hypothesis was that we can get to self-funding. It’ll take 100 groups, which means 100 meals every weekend. Each group will have 100 members and all of them will pay £5 per month. That means £50,000 per month to pay for our team and operating costs. And the whole thing will take us two years.

This was a plausible hypothesis. We made financial projections and growth forecasts. There were spreadsheets and milestones.

It was also a guess. You can tell because it’s full of suspiciously round numbers. It’s OK that it was a guess. All business plans are guesses. All guesses contain assumptions. Some assumptions are riskier than others.

We decided to build Local Welcome by focusing on the riskiest assumptions first.

These were our riskiest assumptions in January 2019. We assumed that we could do all of these things as part of getting to self-funding. If any one wasn’t true then we didn’t have an operating model.

We wanted to face the riskiest assumptions early so we could know sooner rather than later whether we had a shot at getting to self-funding.

I’m going to take you through how we tackled these risky assumptions.

In January 2019 we set out to start groups in cities we don’t live in.

We set four February launch dates in Cardiff and Birmingham. None of us had ever lived there. We did some things to make it easier for us to launch:

Hired community halls for two dates in Cardiff and two dates in Birmingham (rather than trying to find a forever venue).

Went up on the train, carried the equipment, bought the food, and led the meals (rather than looking for local leaders).

Partnered with Migrant Help to find refugee guests staying in nearby hostels (rather than connecting with wider communities).

The big thing we were testing was whether we could find local people, in new cities, who were interested enough to come to our meals.

We ran an experiment using Facebook adverts. We showed three adverts to people who lived within 5 miles of the meals. Each advert linked through to an Eventbrite page which had 12 free tickets to the meal.

It worked! The Facebook adverts worked so well that they are the same adverts we use today. We’ve found more than 3,500 people like this.

By the end of February we knew we could start groups in cities we don’t live in. We knew how to connect with local demand.

In March 2019 we set out to recruit capable paying local leaders. Up to then we had been leading meals ourselves.

We needed capable local leaders because our team of six couldn’t keep leading meals forever. We needed local leaders to pay or we wouldn’t have a financial model.

We tried asking the 48 people from the Cardiff and Birmingham meals in February to be leaders. We did a clumsy pitch but only two people signed up. This 4% conversion rate wasn’t good enough: we can’t be running four meals to find two leaders!

There were two problems with our clumsy pitch. People were not expecting to be asked and they didn’t know what being a leader involved.

We ran an experiment when we launched in Thornton Heath in April. We intercepted people after they clicked on our Facebook adverts and did three things:

Asked whether people were leadership or membership material. Amazingly, 20% of people said they were up for being leaders.

Called them to explain Local Welcome and answer questions. This built trust, helped us understand motivations, and built their commitment to our idea.

Invited only these potential leaders to the first two meals in Thornton Heath. We left the members on the shelf until a later date when we had found leaders.

This worked! 10 of the 20 people from the first two meals in Thornton Heath signed up and paid to be leaders. This 50% conversion rate was more like it. Within weeks these leaders were leading meals themselves.

By the end of April we knew we could recruit capable paying local leaders.

In May 2019 we set out to get local people to pay £5 per meal. Up to then we had been doing free tickets to meals.

This felt like our riskiest assumption. When I talked to people in charities they would smile and edge away as they realised this was the foundation of our operating model.

There are broadly two mental models people have for charitable giving:

Donating. For example, you set up a £10 direct debit to Oxfam and this goes out every month. You are giving money.

Volunteering. For example, you go to a food bank one evening a month to pack and distribute food. You are giving your time.

We were asking people to give both money and time. This doesn’t fit into either of these mental models. And I’ve learned to be sceptical of any innovation that messes too much with pre-existing mental models.

We ran an experiment in May in Cardiff, Birmingham, and Thornton Heath. We turned on paid tickets in Eventbrite. It took less than five minutes.

It worked. People bought tickets. Every meal since has been all paid tickets. We’ve sold more than 11 of 12 tickets as a rolling average.

We never asked anyone whether they would pay. Or how much they would pay. I’ve done this research before, back in agencies, and got burned. When it comes to price, the gap between what people say in research and what they do in real life is huge.

Being burned like this convinced me that the only way to find out about price is to offer something valuable and ask people to pay for it with their own money. We could have prototyped and tested things in the lab but I insisted that we build a real service from day one so we could get to our riskiest assumption quickly.

By the end of May we knew we could get local people to pay £5 per meal. There was huge demand we could tap into wherever we went.

In June 2019 we had to stop and remove our team from running meals. We hadn’t realised this was a risky assumption until we found ourselves stuck in June.

In June we ran two meals in each of Cardiff, Birmingham and Thornton Heath. Local leaders were leading the meals but we still had to go along ourselves. We were the only ones who could open the venue (alarm codes), do attendance (lists of names), and answer difficult questions.

With a team of only six people we couldn’t add meals to existing groups, let alone open new ones. I was starting to hate Sundays too.

We ran multiple experiments. It took ages. It was slow and painful.

We tried giving instructions to leaders via the web because it was easy to maintain. Leaders didn’t want to use their smartphones at the table though. Food hygiene was a problem as phones aren’t sanitary. Social perception was a problem because it felt like leaders were looking at Instagram. And we were attracting a diverse group of leaders who didn’t all have smartphones or feel confident using them.

We tried giving the same instructions on paper. We designed plastic A4 sheets and clipped them into pink ring binders. This worked beautifully. Leaders took the sheet they needed and put it back afterwards. They cleaned the sheets before and after use. They felt socially present. But it didn’t solve the problem of secret information. We can’t have burglar alarms and sensitive names floating around on bits of paper.

We tried creating a ‘primary leader’ role. One of the leaders had a briefing with us to get the secret information like burglar alarms and lists of attendees. They were then responsible for keeping that information safe. Finally, at the end of July, we stopped going to Cardiff, Birmingham and Thornton Heath. We opened Derby in August.

By the end of August we knew we could remove our team from running meals. We went on to launch new groups in Liverpool (September), Wakefield (October), Glasgow (November) and Belfast (December).

In September 2019 we set out to prove our meals have meaningful impacts. We knew anecdotally that our meals had good outcomes but we didn’t have any data.

People in the charity sector were appalled that we’d been running meals for so long before looking at outcomes. Outcomes are how the sector measures value. They underpin funding from trusts and foundations.

There were two reasons why we didn’t look at outcomes earlier:

One reason was methodological. Using agile and lean methods mean we try things, learn from what happens, and make changes to our model. Our model changed loads between January and September. I didn’t want to spend months measuring outcomes that came from an outdated model.

The other reason was contextual. Our outcomes build over time. You don’t come to a meal for two hours and instantly feel less lonely or more confident. It takes coming back again and again. We needed to run for a while to see outcomes.

By September we had six groups running on a stable model. Ready for outcomes.

We ran an experiment. We set a date in November, booked a room, and invited powerful funders to an event to unveil our outcomes.

However, in September we hadn’t done any of this work yet. We spent the next two months running around and settled on two things:

The Social Impact Consultancy did some independent research into the impact of meals on leaders, members and guests. They observed and did interviews. They came back with an impartial third party report into the impact of our meals.

I leaned on my researcher past to do a survey of leaders and members. We got more than a 50% response rate which still amazes me. We asked questions about demographics, motivations, and outcomes they’d experienced over time.

We did this on top of opening a new group each month. It broke me. After the event I took an unscheduled week off and did nothing. I didn’t recover until January. I told myself ages ago to avoid burning out and this was a reminder of why that matters.

At least we managed to prove our meals have meaningful impacts. I’m going to share the three impacts that mean the most to me.

This is a refugee guest talking. They’re saying that for two hours they were able to stop thinking about the things that usually preoccupy them.

We were expecting this outcome. Our meals are designed to get people to focus on a task, and on interacting with others, and this ends up feeling like a flow state. The world ebbs away for two hours.

It was still important for our team to see evidence of this outcome.

This is one of our local members. They met a refugee guest at a meal, realised this person needed something, met up outside of the meal, and then became friends.

We had hoped for this outcome. It’s why Local Welcome meals are important. What starts on the table ends up going beyond the table.

It was massive for us to see evidence of this outcome.

This is one of our local leaders. They’re saying that being a leader made them more confident. They applied for, and got, a promotion that had a material impact on them.

We hadn’t expected this outcome. I thought that the 20% of people who said they were up for being a leader were already leaders. Maybe at work. Maybe in a youth group or scout troop. Maybe in a large family.

Yes, maybe half are leaders already. But the other half are not leaders, or don’t see themselves as leaders. Local Welcome puts people in the lead and this carries over into their everyday lives. I said I’m obsessed with having an impact. This is the first time in my career I’ve felt it’s working.

There’s something else here too. We saw the same outcomes - decreased loneliness, better understanding of others, increased confidence, stronger social connections and better social capital, changed eating habits - across everyone at our meals.

I said we’re not doing things for refugees. That’s easy to say. Our impact work showed that Local Welcome meals have the same impacts on everyone that comes to them. The meals are not just for refugees, they’re for everyone.

By the end of November we could prove our meals have meaningful impacts.

In January 2020 we set out to find refugees to come to our meals. But how have we been running for a year if we can’t find refugee guests?

We used a hack in 2019. There are eight initial accommodation centres in the UK for people claiming asylum. People stay for two months before being ‘dispersed’ around the UK. Our first eight groups opened next to these hostels and we partnered with Migrant Help to find refugee guests.

This was convenient for us. It let us focus our attention on starting groups, finding leaders, getting members to pay and proving impact.

It was also problematic. These refugees were a subset of the wider population. Their English was poorer because they had just arrived. They only stayed for two months so longer-term connections were hard. And we were picking refugee guests up from hostels which felt infantilising. It wasn’t reducing the power dynamics at our meals.

Since January our meals have been open to all refugees in our cities. They get their own tickets. They turn up themselves. Just like our members. It’s much more equal.

But it’s also a lot harder to make it work.

Our first experiments focused on infrastructure for guest tickets:

We tried using Eventbrite and email because we use those things for members. This approach failed. Eventbrite is hard to use even if English is your first language. Lots of refugees don’t have internet access, let alone email addresses.

We tried using text messages. This worked well. Most refugees have mobiles and can get texts even with no credit. If they don’t have a phone a friend or caseworker can get their ticket for them and give them the number.

Our next experiments were about increasing awareness among refugees:

We tried a ground-up approach to get in touch with organisations working with refugees. We asked local leaders to introduce us to people and snowballed out. We’ve been mapping all the services in these cities and asking them for help.

We tried sending local leaders to drop-ins where refugees congregate for legal advice or social activities. Our leaders participate in the session, talk about Local Welcome, and invite refugees to come along. This works well.

But it’s March 2020 and we still don’t know if we can find refugees to come to our meals. Yes, we’re issuing more guest tickets, but it’s a lot of manual work and drop-out rates are high. It’s our riskiest assumption. If we can’t work out how to do this then our operating model is sunk.

Which means we’re not ready to scale to 100 groups with the same team.

We opened eight groups in 2019. But that wasn’t about scaling up, it was more about learning whether we have a viable operating model. Each group was an experiment. Soon we’re going to see whether we can operate more groups with the same team.

People ask me if it is even possible to scale to 100 groups with the same team. The truth is that I don’t know.

On my good days it seems like a clear path. We automate loads. We devolve more responsibility to leaders. We get word-of-mouth awareness going. We remove the problems that create support tickets.

On my bad days it seems impossible. We’ll never find enough venues. We’ll never get the guest turnout. Our team will never be able to operate ten times as many groups without growing.

I just don’t know. But looking back over the last 12 months gives me hope.

A year ago these things were all risky assumptions. We didn’t know how to do any of them. At some point, each of these things has kept me awake at night. All of them seemed impossible at times.

But our tiny team has worked through these risky assumptions, one painful experiment at a time, and we’ve learned how to do new things.

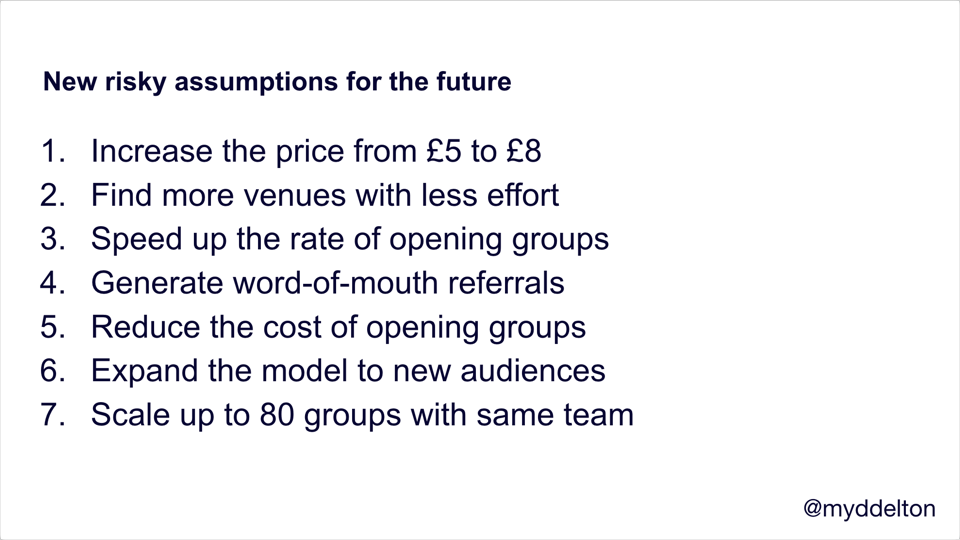

We’ve learned is that our original hypothesis wasn’t right. So we’ve been updating it.

We can still get to self-funding because nothing has ruled it out yet. It’ll take 80 groups rather than 100 groups (there is maths but I’ll spare you). Each group will have 30 leaders (who pay monthly subscriptions) and 48 members (who pay for meal tickets). They’ll have to pay £8, not £5, because we learned how much it costs us to start a new group. That gives us £49,920 per month to pay for our team and operating costs. But it’ll take us three years which is a big deal because our Lottery money runs out this summer. We have been out trying to raise more money.

This revised hypothesis is a guess. An informed guess because we’ve learned things. But still a guess. And that’s still OK.

It means we have a new set of risky assumptions.

We don’t know how to do any of these things yet. We have plans. But we don’t know.

This is what we’re working on for the next 18 months. Because, at Local Welcome, we structure work by tackling our riskiest assumptions.

Before I finish I want to share five things that I’ve learned in the last year.

OMG. I’ve learned that everyone has an opinion about how I do my job! Why did no one tell me this is what being a product manager means?

My team has opinions. Our leaders, members and guests have opinions. My mum has opinions. Anyone I meet at a party, or at a conference, is telling me their opinions within two minutes. People even have opinions before coming to a meal - I had a 14 paragraph email from someone who took great care in tearing down every aspect of our proposition despite never having been to a meal.

That’s OK. Feedback is a gift. I smile, I nod, and I listen. I’ve learned a ton of things from people’s opinions. Things that have changed our direction.

But it’s also emotionally hard. Like on a Tuesday afternoon, when I’ve spent two days dealing with a customer service disaster at the weekend, and I get a 14 paragraph email from a stranger telling me the things I’m doing wrong. It makes me want to cry.

I have a newfound respect and empathy for product managers. Especially the ones I’ve worked with. Because I definitely had opinions about how they did their jobs.

I’ve learned that putting out fires is a valid design approach. When doing experiments we’re creating a bare-bones service that just about works. Every part of the service is ‘good enough’ and we come back and fix bits that are broken (e.g. putting out fires).

What I had never realised is that you rarely come back and fix the parts that are not broken. Things that work stay as they are. So we’re full of bare-bones ‘good enough’ design decisions that I find horrifying and embarrassing:

The agency designer in me is horrified because we’re not thinking it all through upfront, documenting everything, making it feel consistent, or having a solid rationale for each element. That’s what I used to sell.

The in-house designer in me is horrified because I got so used to agile teams failing to come back and iterate that I ended up doing upfront design work as a rational defensive measure.

My perspective has shifted now that I’m making these decisions. We have limited time and money and we need to spend it on what’s most important. That is usually moving to the next risky assumption rather than assuaging the guilt of all my inner-designers.

So I tell myself it’s OK that lots of things are a little bit broken most of the time.

I’ve learned not to automate things until I know they work. This was painful because I’ve spent years telling teams not to build technical solutions until they understand how people will use them.

Then when I joined Local Welcome I spent weeks designing and building a powerful, elegant, automated system to sign people up to be leaders. Nudges, emails, calls-to-action, flows. It was beautiful. It didn’t work. Not a single person signed up.

It didn’t work because I didn’t know how to sign people up to be leaders. To find out I called people up and asked them to be leaders. Over time I learned how to ask the question in an email. And later still I was able to automate the emails. Once I knew how it worked, I could automate it.

That’s our pattern now. When we face an unknown we put a human on it until they figure out how to do it. Then we work out how to automate it.

I’ve learned how powerful experiments are. We tackled our riskiest assumptions using experiments. We opened new groups with different start conditions. We tried things in one group before another. We sent different things to different people. We failed lots.

I’ve had a long-running suspicion of the word ‘experiment’ though. So let’s be clear.

By ‘experiment’ I just mean that we changed something, paid attention to what happened, and learned stuff. When it came to learning we used intuition and gut feel as much as hard data. I’m OK with this, because when we’re looking at our riskiest assumptions then our experiments have big, obvious, pass/fail type answers anyway.

By ‘experiment’ I don’t mean that we set up rigorous tests where we isolated single variables and used statistically significant sample sizes to tell us the objective truth about the world. Maybe we’ll run those kinds of experiments when we’re operating at large scale. Maybe not.

I’m not mad about words like ‘experiments’, ‘hypotheses’ and ‘assumptions’ either. These are borrowed from science and they can encourage the macho unthinking bullshit of scientism. We’ve all seen people - often overconfident men - who treat numbers-from-any-source as more important than stories, experience and hunches.

But experiments are powerful. As long as we remember that we’re not doing science.

The final thing I’ve learned is something I’ve been learning for years. When it comes to multidisciplinary teams it’s the shared goal that matters more than anything. That’s what allows us to be more than the sum of our parts.

I’m going to get to this in a roundabout way.

This is an album called Screamadelica by Primal Scream which meant a huge amount to me as a teenager in the mid-90s. My favourite track on it was Come Together. This was produced by Andrew Weatherall (who died recently, much too young) using a sample of a young Jesse Jackson speaking at WattStax in 1965 to tie it together:

Today on this program you will hear gospel,

And rhythm and blues, and jazz

All those are just labels

We know that music is music.

This sample had cosmic significance for 16-year-old me. The words ring in my head. They forever changed how I listened to music, thought about music, made music.

I’ve realised, recently, that they still have cosmic significance for 42-year-old me.

When people talk about agile, systems thinking, user-centred design, lean, extreme programming - my mind says ‘all those are just labels’. When people talk about product management, service design, interaction design, information architecture, user experience design, user research, content design - my mind says ‘all those are just labels’ too.

Labels can help us learn our craft, talk to each other clearly, and save time by using a specialised vocabulary. But labels can also divide us if they become part of our identity. They end up creating us-and-them groups. I know because I was part of this at GDS in the user research team. It happens.

I think we talk too much about labels and not enough about our teams’ shared goals.

I learned how important shared goals were when I was running discoveries at GDS. We went round in circles trying to find out everything about everything. Eventually someone sat me down and said your goal is to decide whether to pursue this opportunity or not. Overnight we all started pulling as one team in the same direction.

You already know how important shared goals are because I’ll bet that you’ve worked on teams that don’t have them. Your team is full of lovely, bright, capable people but you’re all going in different directions and it ends up being a horrible nightmare. Multidisciplinary teams need shared goals to work well together.

It’s why I don’t hold with “start with user needs” much any more. Teams start with a shared goal. Maybe that goal comes from what you know about people. Maybe it comes from a burning desire in your heart. Or a politician elected on policy intents. Or even just a plain old profit motive. Whatever. We start with the shared goal.

This is our shared goal at Local Welcome. In two years we are trying to operate an impactful, inclusive ritual that is membership-funded.

We wrote this goal together. We revise it when we need to. We use it as the basis for all our roadmaps. We refer to it all the time. This is our goal.

I talked about our hypothesis. It’s meaningless to talk about our hypothesis without knowing our shared goal. Our hypothesis is one of many (many) hypotheses to achieve our goal to operate an impactful, inclusive, ritual that is membership-funded.

This whole talk has been about tackling our riskiest assumptions. The risky assumptions come from the hypothesis which comes from the shared goal. Our whole team is able to trace their work back to our shared goal at any time. It’s powerful.

Looping back to Primal Scream and this labels thing.

This is why I love it when our team questions the ways we work. When they say let’s stop doing sprints. Or let’s change how to do retros. Or maybe this whole bit of work doesn’t need any user research. They’re saying…we know that these are just labels.

I love it because it shows our team isn’t focused on the labels. Instead they’re thinking about our shared goal. They’re saying…we know that music is music.

Come together as one.

OK, enough, let’s wrap this up.

Building Local Welcome by tackling our risky assumptions has been scary. Every day we come into work facing into the abyss. Thinking if this thing doesn’t work then we don’t have an operating model.

There are other, less scary, ways to work. I’ve been on projects where we didn’t face our riskiest assumptions until the end. We spent most of the time doing fascinating, interesting and compelling design work. Towards the end we tried to retrofit reality to our work. Always without success.

I’m convinced that facing our riskiest assumptions has been a good way to build Local Welcome. I wonder if that will change as our service matures? I guess we’ll find out.

I’m going to end with a poem.

It’s from a book which is called The Poetry Pharmacy. It’s a peaceful, healing book. Just before I started at Local Welcome I took this off a bookshelf in Bristol and it fell open on this poem.

I’m open to weird signs from the universe these days. So I decided there and then that this poem was going to sum up my Local Welcome experience. It has.

Here it is:

Come to the edge.

We might fall.

Come to the edge.

It’s too high!

COME TO THE EDGE!

And they came

And she pushed

And they flew.

Christopher Logue

Thank you.

Let me know what you think on @myddelton. Local Welcome is also Ben Pollard, Claire Brown, Celia Mellow, Andrew Chaplin and Efe Harut. We did this together.