People in the lead

Local Welcome puts people in the lead. We run meals across the UK that are led by groups of leaders from local communities. We change and shape our meals and our organisation in response to feedback from our leaders, members and guests. Our meals have a distinctly local feel despite us being a national charity.

The Lottery, who fund us, care about people being in the lead. “When people are in the lead, communities thrive” is how they put it. It’s true! Our meals attract new people to leadership, increase the confidence of leaders, build connections that didn’t exist before, and reduce loneliness and isolation for the people that come. These things help our communities thrive.

But “people in the lead” is not always a straightforward concept for us. Although we do put people in the lead at Local Welcome, we’re also clear that it does not mean:

letting people do whatever they want

responding to everything people say

giving people control over strategic decisions.

This sounds counter-intuitive, like maybe people are not in the lead at all. I get that. I’ve been grappling with this tension for a decade as a user-centred designer who tries to balance the needs of people against the goals of organisations so that both are met. It’s hard to get this balance right. But it’s important to find a balance.

This post is about how we put people in the lead, where there are tensions, how we resolve these, and where we need to do things differently. This isn’t the only way to think about people in the lead (far from it!) but I hope that sharing what we’ve learned at Local Welcome is helpful.

People lead our meals, but there are limits to their power

People lead Local Welcome meals, specifically a small group of leaders who all live within a mile or two of the venue. Four leaders turn up at 11am to set up the space and lay out the food. From noon they welcome everyone and lead the group through cooking, eating and tidying up. Then they close up and leave by 3pm.

Our leaders are in charge for those four hours. They take control of activities. They set the tone and resolve conflicts between people. They fix problems when the food doesn’t arrive. They are our people in the lead.

But putting people in the lead doesn’t mean they can do whatever they want. There are clear boundaries because often the best intentions of individual leaders conflict with the wider goals of Local Welcome.

For example, we want diverse groups of leaders. We have designed Local Welcome to open up leadership to as many people as possible. One way is that there is no hierarchy of leaders in a group - so we can minimise the way that power dynamics too often favour the bold. Another way is that we limit leader involvement to four hours each month - so we can maximise the chance that those with busy lives will feel just as much a leader as those with more free time.

So when a leader starts assuming overall control, or starts tasking other leaders, we ask them to stop because we can’t attract a diverse group if certain types start to dominate. Or when another leader spends hours preparing extra food for our meals, even though we love their intent, we ask them to stop because we worry about losing leaders who can’t put in extra hours and feel guilty as a result.

This is just one example of a tension around people in the lead. There are many others. Our leaders are in charge, but with limits to their power, because we are balancing individual needs against the needs of the group. I’m not saying we always get it right, but we do spend time working out the boundaries and being clear.

And, honestly, there are some leaders who chafe against these boundaries and leave Local Welcome. That’s OK. There are lots of different ways to lead in your local community and our meals are only one of these.

We’re led by people’s feedback, but we don’t always react

People lead the constant evolution of Local Welcome by giving us direct feedback. Not just our leaders, but also our members (local people who pay to come) and our refugee guests (people seeking sanctuary who come for free).

We get this feedback in many ways. It’s important that we never ask people what they like or dislike because avoiding preferences is the first rule of user research! Instead we use these ways to find out what’s causing us problems:

Leaders tell us what’s working and not working after every meal

Members give feedback by email and refugee guests by text message

Our team goes and takes part in meals to observe things in person

Third party researchers go out and assess our outcomes and impacts

I receive personal emails and people aren’t shy about saying what’s wrong!

We process this feedback every Monday at our whole-team debrief. This has led to changes like printed rather than digital instructions, new recipes, better experiences for first-timers, new methods for tidying up, and countless other improvements.

But being led by people’s feedback doesn’t mean responding to everything that people say. There are three reasons we don’t always act on what we hear:

We have a tiny team of six people. We focus our team only on the things that are most important right now. Lots of problems go unaddressed because they’re not (yet) important enough to prioritise above everything else. We had people asking for new recipes for more than a year before that became important enough for us to spend several weeks responding to recently.

There are some things that only our team can see. Reasonable suggestions (like leaders bringing homemade desserts) are ignored because we’re aware of factors that are invisible to the person suggesting it (leaders bringing food complicates food hygiene and it can make time-poor leaders feel lesser-than). We also ignore suggestions to provide activities for children because we prefer to involve them, not provide a separate creche-style experience.

It’s impossible to respond to every piece of feedback. Different people have different opinions that can’t always be reconciled. Some of our leaders want less structure so that they can improvise more, other leaders want more structure so that they feel secure about exactly what’s going to happen. Both are reasonable, but we say no to both in the name of balance.

Regardless of whether or not we respond to feedback, we are open and honest with people about what we’re doing. It’s hard telling people that their suggestions won’t get acted on for a while, and harder when we explain that things won’t change at all, but by being clear about our reasons we bring our leaders into the conversation.

And, again, sometimes people leave Local Welcome because we won’t make the change they are asking for. We’re always sad to see people leave, but we’re OK with it as long as our meals keep getting better and more inclusive as a whole.

Strategic decisions are led by our team and our trustees

Finally, there’s a whole area of leadership at Local Welcome where people are not really in the lead. Big strategic decisions like making financial forecasts, deciding which funding to apply for, shaping nationwide growth plans, setting HR policies, or even deciding what to do while we can’t run meals during the pandemic.

These decisions are led by our team and trustees. Mostly there are good reasons for this, but there are some things we need to change too.

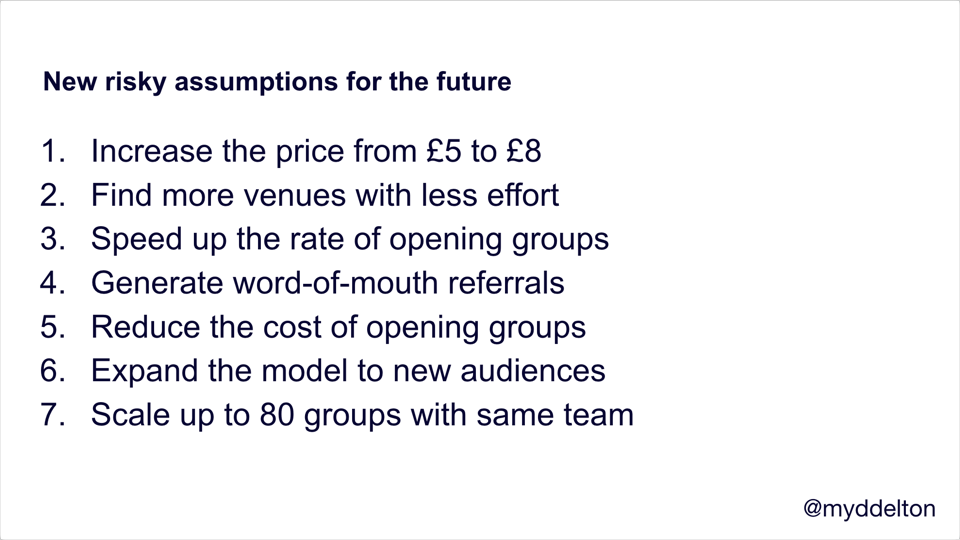

We are a young organisation trying to find a sustainable operating model and we’re changing what we do when we find out what works. Our priority is to be flexible and iterate our model, and setting up effective systems to involve people fairly requires more stability and headspace than we have right now (also, as we flex and iterate, the types of people that we work with are constantly changing). We think it’s OK to make this trade-off while we establish ourselves. Others may disagree.

More specifically, we are pursuing a difficult goal to become self-funded. We are using technology to support meals in 100 locations each week, which means that our meals have to be standardised in ways they would not be if they were run 100% locally. Managing this tension between local leadership and a national model involves trade-offs. Our team and trustees have experience with these trade-offs, and we sit outside the local context, so we take the lead on these decisions.

Of course, there are ways to involve the people that come to our meals in big strategic decisions. We’re planning to explore models for doing that in the future. But they’re not a top priority for us until we’re more established and scaled up.

What is a top priority for us is to improve the diversity of our team and trustees. We think it’s OK for our team and trustees to lead on big strategic decisions as long as we are representative and diverse. But we could be doing better on this because our team is mostly white and our trustees are mostly men. We’re currently finalising fair policies for pay and HR (we’re proud of these!) to go with our inclusive approach to recruitment so that we attract applicants from a wider range of backgrounds when we next recruit. We’re about to expand the number of trustees and recruit a new chair through a new free and fair application process too.

I doubt we will ever get to 100% people in the lead on big strategic decisions and I think that’s OK. But I’m looking forward to working with a more diverse team and a more representative set of trustees in the near future, and I’m intrigued to see how we can involve leaders, members, and guests in strategic decisions one day.

All great slogans contain hidden tensions

Let me try and wrap this up with a personal reflection on “people in the lead” and why it feels important to be honest about the trade-offs it involves for us.

I used to work at an organisation called the Government Digital Service (GDS). One of the core principles at GDS was to “start with user needs”. This was a wonderful, necessary, motivational principle when it was introduced in 2010 because too many government services didn’t think about the needs of users. It’s why I joined GDS.

But, over time, “start with user needs” took on such weight that people ended up making poor decisions by referring only to the slogan, rather than balancing user needs with factors like policy intent, technical feasibility, or budget availability. I spent a lot of time at GDS trying to unpick these decisions and convince people that the real task was to balance these things. A slogan can’t do the hard work for you.

“People in the lead” reminds me a lot of “start with user needs”. It’s a wonderful, necessary slogan. It’s a powerful injunction to avoid perpetuating charities that are run in a paternal, top-down, we-know-what’s-best-for-people way. It’s a helpful framing of what’s been going wrong for too long.

But “people in the lead” contains tensions too. If it means letting people lead without boundaries we run into problems. If it means responding to all the feedback we’ll never make any progress. And if it means involving people in strategic decisions early in the life of our startup charity it creates more overhead than we can deal with.

At Local Welcome we live with these tensions. We care deeply about people being in the lead - our whole model is centred around people leading our meals - but we know we have to balance having people in the lead against achieving our organisational goals. It’s difficult, and we don’t always get it right, but we’re learning.

This post is reproduced here with the kind permission of Local Welcome. Let me know what you think on @myddelton.